Managed Deficit Irrigation Scheduling in Grain Sorghum to Enhance Yield on High Plains

This tip was provided by:

Jourdan Bell, AgriLife Extension Agronomist, Amarillo, 806-677-5600, jourdan.bell@ag.tamu.edu

High Plains

Managed Deficit Irrigation Scheduling in Grain Sorghum to Enhance Yield

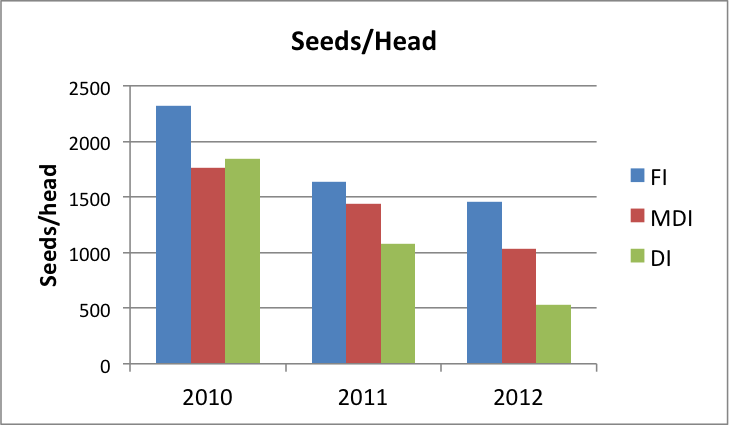

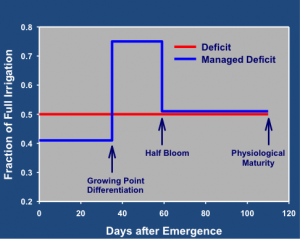

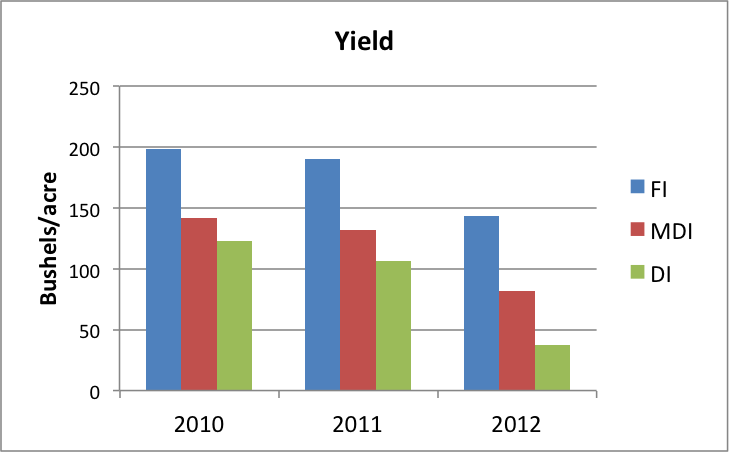

The ample rainfall during the 2015 cropping season has allowed many Texas High Plains producers to significantly reduce their number of irrigations, but in an average year, irrigation is necessary to minimize production risks. However, on the Texas High Plains, well capacities are declining and producers have to make critical decisions on how to manage limited water resources to optimize production. In grain sorghum production, irrigation is commonly applied at a fraction of the crop water requirement throughout the season (deficit irrigation). However, in a three-year study on a clay loam soil at Bushland, our research found that concentrating irrigation during critical growth stages (managed deficit irrigation) maximized yield. Using a managed deficit irrigation strategy, yield was maximized by increasing the number of seeds per panicle in two of three years. Grain sorghum yield is a function of the number of seeds per head (63%), number of heads per acre (30%), and seed size (7%). While peak water use occurs around boot, irrigation targeting the critical growth period between growing point differentiation and half-bloom is the critical period to increase yield with this strategy because seeds per head make a proportionally higher contribution to yield. Growing point differentiation occurs approximately 30 days past emergence when there are seven to ten leaf collars visible. At growing point differentiation, the number of seeds per head is being determined. Half-bloom occurs when 50% of the plants are blooming.

With a managed deficit irrigation strategy, two early season irrigation events prior to growing point differentiation were eliminated in comparison to a deficit rate at 50% of the crop water demand. From growing point differentiation through half-bloom, irrigation was approximately 75% of the crop water demand, and from half-bloom through reproductive maturity, irrigation was applied at a deficit rate. While management was intensified, the cumulative seasonal irrigation was comparable between the deficit and managed deficit strategies.

By reducing the early season irrigation events with a managed deficit irrigation strategy, early season evaporative losses from the soil surface prior to canopy closure were minimized. And while deficit irrigation was a fraction of full irrigation (100% crop water demand), the same irrigation depth was applied but at different intervals in the Bushland study. In doing so, evaporative losses of irrigation intervals less than one inch were also minimized. While this complicates irrigation scheduling, it was a more valid approach than applying frequent irrigations of one-half inch or less. Grain yield and seeds per head were greatest in all years under full irrigation; however, these components were significantly greater under the managed deficit irrigation than the deficit irrigation in two of the three years. Under normal precipitation and in-season temperatures (2010), the effect of irrigating at the critical growth stages was not significant because the crop was not stressed during the period of growing point differentiation. However, under extreme drought and heat stress of 2011 and 2012, yield and seeds per head were significantly greater. This research and the associated management implications provide a valid management strategy to optimize irrigated grain sorghum yield.

While this strategy is valid on fine textured soils, it needs to be evaluated on a coarse textured soil with nominal soil moisture storage capacity. Additionally, this strategy requires a greater well capacity than would be required by a traditional deficit strategy if irrigation a large area. However, it is ideal in a split pivot scenario and allows the producer flexibility in irrigating secondary crops.

Grain Sorghum Recovery From Saturated Conditions & Sugarcane Aphid in High Plains

This tip was provided by: Ronnie Schnell, Ph.D., Cropping Systems Specialist, College Station, (979) 845-2935, ronnie.schnell@ag.tamu.edu

Grain Sorghum Recovery from Saturated Conditions

Central and North-Central Texas

Repeated rain events during May resulted in soils being saturated, or even flooded, for extended periods of time for many sorghum fields across Texas. Rains have continued through June for many areas as well. At that time, many wondered what the impact would be on grain yield, if any? Predictions of final yield are difficult to produce for such an unusual situation but are important when deciding how much to invest to protect the crop from late season weeds and insect pests. Figure 1 shows grain sorghum in north central Texas on June 12, after two weeks of dry weather. This crop showed severe stunting and yellowing the previous week after over a month of repeated rain events and saturated conditions. This field received between 15 and 20 inches of rain during the month of May alone. However, new leaves had emerged from the whorl with good size and color by June 12.

With signs of recovery during early June, actual yield potential was still uncertain. Revisiting this field on June 30 revealed that significant recovery had occurred and substantial yield potential was available (Figure 2). An additional 6-8 inches of rainfall distributed throughout June with sunshine likely helped this crop recover, which had a shallow and damaged root system from May rains. Now it is obvious that there is yield worth protecting as this crop continues through grain fill stages.

Several issues have been reported throughout the region, including stinkbugs, midge, head worms and sugarcane aphids. Uniformity of crops within fields will create challenges for management of these pests (Figure 3). Sugarcane aphids are present, but numbers are generally below economic thresholds (http://txscan.blogspot.com/). It is uncertain what aphid populations will do later in the season. Therefore, it is important to treat pest problems that are present, such as stinkbugs or midge, when economic thresholds are reached (https://insects.tamu.edu/extension/apps/sorghumricestinkbug/index.php). Scouting will be important, making sure to check all areas of the field that are in various stages of development and to estimate the proportion of each field in contrasting stages of development.

Figure 3. Various stages of development present within sorghum fields along terraces due to wet conditions (June 30).

Sugarcane Aphid

High Plains

As reported in the newsletter above, please click here to view more information on the sugarcane aphid in the High Plains.

Grain Sorghum Field Conditions are All Over the Map

Statewide

As Dr. Ronnie Schnell noted in the previous Sorghum Tip, Central Texas flooding conditions and saturated soils are cause for concern on sorghum growth and development. Texas High Plains grain sorghum that was planted early (late April and early May) has seen unprecedented rainfall as well though saturated and flooding conditions are less likely. Either case can lead to a lot of foliar and growth & development symptoms. It is difficult to know what we are looking at as some symptoms may appear similar.

For example, the traditional “interveinal chlorosis” that is associated with iron deficiency, and which grain sorghum is much more susceptible to than most crops, is normally green veins in the leaves with yellow in between. But this is not the only nutrient that may cause such a symptom. Zinc and sulfur can cause symptoms that might be confused with iron deficiency (yellowing, less pronounced striping in the leaves). Add in the general yellowing that can occur from nitrogen deficiency, and you have a difficult time deciding what is occurring. Tissue testing can be conducted, but sometimes the “normal” ranges in the leaves, for example, may not give you an accurate indication. And what standard leaf ppm is being used as a reference? These reference levels are not all the same.

Though this publication is dated and the pictures are old, I find this 1980s Australian resource “Nutritional Disorders of Grain Sorghum” to be as thorough as any in the description of nutrient deficiency and toxicity symptoms. See http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/118045/2/2.pdf

Waiting 7-10 Days…

When soils are flooded, temperatures are cold, or you have had a hail, sometimes 7 to 10 days is all it takes to “tell the story” of a grain sorghum crop or other crop turning around. Examples in Central & South Texas, the Texas South Plains, etc. currently reveal what draining and drying soil, warmer temperatures, and sunshine can do for a crop. Much of the Texas sorghum crop has a limited root system due to either flooding, as Dr. Schnell noted, or simply not needed to root deeply for moisture. But as drier, aerating conditions in the soil return, root volume will begin to expand. This often fixes a lot of foliar leaf symptoms—watch for new leaves appearing in the whorl and recently emerged leaves to return to near normal green coloration. This is a good sign.

Sorghum and Brace Roots—Key to Standability

The above picture, courtesy of Tate Newsom in Terry Co., shows grain sorghum that has leaned over from a strong wind. I would not call this lodged sorghum (which often involves stalk breakage). This sorghum is planted flat, and is at a stage of growth where the brace roots are just starting to emerge from the base of the stalk. Given time, these roots will anchor the stalk and stand the plant up. Where grain sorghum can struggle in this type of situation is 1) the sorghum is planted on top of a bed (that does not fit the type of plant and the root system of grain sorghum, but it works OK for taproot crops like cotton); you can’t very well throw soil with cultivation ‘uphill’ to cover the brace roots, and hard rains can wash soil away from brace roots entering the soil; b) soils are hot and dry, and thus roots don’t as easily enter the soil. If you still use cultivation for weed control, when you throw soil around the base of the sorghum plant, the brace roots are then already in the soil when they emerge. This is a win-win for grain sorghum and the producer, and you may have buried a few small weeds in the process.

Fading Weed Control from Pre-Plant/Pre-Emerge Herbicides

We are receiving numerous reports that “weeds are coming” where excessive rainfall has occurred and early atrazine (or propazine, particularly on sandier soils in a cotton rotation) appear to have shortened weed control. Be ready to promptly address in-season weed control needs. Many producers are well past the window for using 2,4-D or dicamba. See the earlier June edition of Sorghum Tips for additional in-season options. Could you possibly consider additional atrazine if sorghum is still 12” tall or less? This might be a consideration, but how readily you would decide to add more might depend on your crop rotation goals. Talk to your chemical dealer, company rep, or our AgriLife weed scientists if you need options. AND… scout your fields for weeds. They grow faster than our kids! Do your best to not let them get away, remembering the smaller weed size is easier to control. I assert that if you ever find yourself asking/doubting “Should I go ahead and apply my weed control?…” based on the size of your weeds, you should probably go ahead and apply.

Impact of Flooding or Saturated Conditions on Sorghum

This tip was provided by:

Ronnie Schnell, Extension Agronomist, College Station, 979-845-2935, ronnie.schnell@ag.tamu.edu

Calvin Trostle, Extension Agronomy, Lubbock, 806-746-6101, ctrostle@ag.tamu.edu

North, Central & Coast

Impact of Flooding or Saturated Conditions on Sorghum

Recent rain events have resulted in flooding or significant ponding of water in many sorghum fields across Texas. While low-lying areas may be flooded, other areas of fields may be saturated for extended periods of time. How long can sorghum survive under saturated or flooded conditions? What impact will these conditions have on grain yield, if any?

Oxygen is required by plants for respiration, including above ground (shoots) and below ground (roots) plant tissue. Respiration is the process where plants metabolize sugars, producing energy needed for growth and development. Soil contains about 50% pore space that is occupied by air and water. Flooding increases the proportion of pore space occupied by water and reduces exchange of air between the soil and atmosphere. Deep ponding has the same effect on above ground tissue. Oxygen does not easily move through water so saturated or flooded conditions will limit oxygen availability to plant tissue, especially roots. This can have detrimental affects on plants.

The growth stage of the crop will influence the plant’s ability to withstand flooded conditions. Younger plants are more susceptible to damage or death by flooding, especially when the growing point is at or below the soil surface. Younger plants (growing point) are easily submerged compared to older, taller plants. Higher temperatures will exacerbate the effects of flooding. Young plants may survive for up to 48 in oxygen limited environments under cool conditions but may not survive 24 hours under warm conditions (>77°F). For this reason, yield loss is typically greater when young plants (< 6 leaves) are exposed to saturated or flooding conditions. Stand loss at early growth stages is a major factor in yield loss. Similar to freeze and hail damage, look for new growth several days after conditions improve to determine surviving plant populations.

Extended periods of flooding or saturation will affect plants of all ages. Root tissue can die and new growth will be stunted or delayed under saturated conditions. Flowering can be delayed for affected plants. Reduction in root volume will reduce the capacity for uptake of water and nutrients during later growth stages. Flooding can induce nutrient deficiency symptoms. Nitrogen will be remobilized from older (lower leaves) to younger (upper leaves) resulting in yellowing of lower leaves. Purpling of leaf tissue is possible due to accumulation of carbohydrates in the shoot tissue under flooded conditions, a symptom usually associated with phosphorus deficiency. In addition, denitrification and leaching of nitrate can result in loss of nitrogen from soil and potentially reduce yield. Damaged root systems and associated stress can increase the potential for various plant diseases, including root and stalk rot diseases. The degree of flooding will ultimately determine the potential for yield loss.

A brief period of flooding will likely have minimal impact on grain yield, especially for older plants. Repeated or long-term saturation/flooding will increase the potential for yield loss due to a variety of complications.

Statewide

2015 Texas Grain Sorghum Weed Control & Harvest Desiccation Guide

Your most important weed control decision for grain sorghum is always pre-plant/pre-emerge herbicide applications. Prevent weeds in the first place, and catch the escapes or other emerging weed issues later with over-the-top herbicides. For most growers a combination of atrazine and metolachlor (Dual) gives good control, but many growers will substitute propazine on sandy soils and in cotton rotations. The above document has been updated by Trostle/McGinty for use in planning your herbicide program with the active ingredients (and brand commercial names) available to your grain sorghum weed control program. View/print/download the document at http://lubbock.tamu.edu/sorghum.

Sorghum Midge

This sorghum tip was provided by:

Dr. Ed Bynum

Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Entomology, Amarillo

806-677-5600, ebynum@ag.tamu.edu

Statewide

Sorghum midge, Stenodiplosis sorghicola, is a devastating pest of flowering grain sorghum but also coexists on Johnsongrass. This little fly, about the size of a gnat, is orange-red in color and has a unique biology. The midge lives less than 1 day but during that time a female can lay approximately 50 eggs. She will deposit only one egg in one of the flowering spikelets. The next day another brood of adults emerges from nearby Johnsongrass or other previously infested sorghum fields to deposit eggs in new flowering spikelets. So, depending on an individual flowering head it may be vulnerable to egg lay for 7 to 9 days and individual fields for 2 to 3 weeks.

Each of egg infested spikelet will have a midge larvae hatch in it in 2 to 3 days. The larva consumes the newly fertilized ovary resulting in the spikelet not developing a kernel. Depending on the number of sorghum midge present during the flowering period a portion of destroyed spikelets may be scattered among normal kernels or a majority of spikelets may not develop kernels. Insecticides are ineffective at controlling midge larvae once spikelets are infested.

Scouting fields during the flowering period is critical to knowing if insecticide applications are needed to kill adults before they have a chance to lay eggs. The residue from an insecticide application should provide midge suppression for 1 to 2 days after treatment. If adults are still found 3 to 5 days after the first application, immediately apply a second application.

The time to check flowering fields for midge is when temperatures are around 85o F. This could be mid-morning in some areas or afternoon in other areas. Adjusting the time to scout based on the temperature is important because midge are not active during lower temperatures.

Currently, midge activity is relatively low in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, according to Dr. Raul Villanueva, Extension Entomologist. Dr. Robert Bowling, Extension Entomologist, Corpus Christi, reports grain sorghum fields were late planted due to rains and are at least 2 weeks from flowering. Late planted fields in the Blacklands and north Texas regions may also be vulnerable to midge when fields begin to flower, notes Dr. Allen Knutson, Extension Entomologist, Dallas. Rains across the other areas of the state may have delayed grain sorghum planting and could influence midge infestations later in the growing season.

More detailed information about the sorghum midge can be accessed here.

A Potpourri of Grain Sorghum Conditions & Weed Control Decision Awry Due to Weather?

Statewide

A Potpourri of Grain Sorghum Conditions

Sorghum conditions and planting dates in each region of Texas are all over the place. Some grain sorghum in the Lower Rio Grande Valley is in boot stage, and other South Texas sorghum hasn’t been planted. Central Texas is seeing a major delay in planting in some areas due to rain. The lower High Plains, due to good soil moisture, has probably seen the most early (April) grain sorghum planted in a long time, and even more would have been planted but for recent huge rains, which have put stand establishment in jeopardy. What to do?

Local considerations for planting late may include sorghum midge potential with later planting (more on this in our next newsletter), decisions about whether to keep a stand based on healthy, emerged plant population, or how late to plant grain sorghum. Also, with the wide range of grain sorghum plantings and the wet conditions, a lot of symptoms show up in the field that you don’t routinely see. These include nutrient deficiencies, which often correct themselves with the return of drier, warmer weather.

On-Line Nutrient Deficiency Symptoms for Grain Sorghum:

- “Diagnosing Sorghum Production Problems in Kansas (2014), http://www.ksre.ksu.edu/bookstore/pubs/S125.pdf

- Key to Nutrient Deficiencies of Corn and Sorghum, http://cropwatch.unl.edu/soils/keysnutrientdef

- 2009 Kansas State Dept. of Agronomy newsletter, http://www.agronomy.k-state.edu/documents/eupdates/eupdate061209.pdf

Weed Control Decisions Awry Due to Weather?

With delays in planting in much of South & Central Texas, and large rains in the High Plains that have saturated soils where early grain sorghum was planted, your planting plans have been turned on their head. Sometimes this creates issues with crop rotation restrictions, your existing herbicide control may be diminished by huge rains, weeds are running amok where you haven’t been able to plant, or you are now faced with replanting grain sorghum.

As you figure out your plans for weed control in grain sorghum our “2015-2016 Texas Grain Sorghum Weed Control and Harvest Desiccation Guide” will help you learn of additional possible options for weed control in grain sorghum, see http://lubbock.tamu.edu/programs/crops/sorghum/.

If you need assistance in planning and re-planning weed control decisions in grain sorghum, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension has three weed scientists across the state that are trained in weed control who may be able to assist:

- Dr. Peter Dotray, Lubbock, (806) 746-6101, pdotray@ag.tamu.edu

- Dr. Paul Baumann, College Station, (979) 845-4880, p-baumann@tamu.edu

- Dr. Joshua McGinty, Corpus Christi, (361) 265-9203,joshua.mcginty@ag.tamu.edu

Grain Sorghum Seeding Rates for Texas

Tip Provided by: Ronnie Schnell, Ph.D.

Cropping Systems Specialist

Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, College Station

A wide range in seeding rates and subsequent plant populations are used across Texas for grain sorghum production. Seeding rates used by growers range from <20,000 seeds/acre under rainfed conditions in the Texas High Plains, especially when at-plant deep sub-soil moisture is poor, to >90,000 seeds/acre under high rainfall/irrigated conditions downstate. Texas A&M AgriLife Extension recommendations for grain sorghum seeding rates are based on rates needed to obtain uniform and sufficient plant populations to optimize yield. Moisture (including stored soil moisture, projected rainfall and irrigation) is often the factor that ultimately determines the appropriate seeding rate.

Seeding rate has been discussed by Texas A&M AgriLife Extension in previous “Sorghum Tips”, which can be found by clicking on the titles of the tips below.

- Irrigated Seeding Rate Suggestions – May 15, 2012 (High Plains)

- Dryland Seeding Rate Suggestions – June 1s, 2012 (High Plains)

- Narrow-Row Grain Sorghum—Increase the Seeding Rate?: Probably Not – Feb. 6, 2013 (Statewide)

Additional grain sorghum seeding rate information prepared by AgriLife Extension is also found in the grain sorghum pocket production guides (three regional editions for Texas) at http://sorghumcheckoff.com/for-farmer/production-tools/.

Central & North Central Texas Seeding Rate Work, 2014

During 2014, a study supported by the Texas Sorghum Producers was initiated in central and north Texas to evaluate grain sorghum yield in response to a wide range of plant populations and environmental conditions. Field-scale replicated strips were used at five locations with seeding rates that ranged from 30,000 to over 90,000 seeds/acre. All locations started with sufficient soil moisture to depths of at least four feet deep. In-season rainfall ranged from 1.5 inches below normal to about 2.5 inches above normal. Yields by location ranged from about 5,500 to 8,000 lbs per acre. Little if any difference in grain yield was observed for the different seeding rates at most locations.

This trial work demonstrates that lower plant populations (<65,000 plants/acre) were not as sensitive to below or above normal amounts of precipitation compared to high populations (>85,000 plants/acre). In other words, lower plant populations maintained yield under less favorable moisture conditions where yields declined slightly for excessive populations. Often, lower yields for high plant populations are due to secondary issues, such as stalk rot. For central Texas, seeding rates between 65,000 and 80,000 seeds per acre (with about 90% stand) will provide good yield potential while reducing risks associated with higher seeding rates. In drier years, the lower end would likely be appropriate.

Central & North Central Texas — AND Statewide

The above “flat” results of sorghum grain yield in response to increasing seeding rates are not surprising considering sorghum’s ability to compensate for yield across a wide range of plant populations. This is accomplished through increased tillering and larger head size at lower plant populations. This provides a great advantage for low plant populations. Though not all hybrids respond to low plant populations the same way, reduced seed drop and subsequent plant populations allow the plants to adjust (increase tillering and head size) when conditions are favorable.

Huskie Herbicide Update & Rotation Concerns to Cotton

Statewide

Huskie Herbicide Update

Huskie as an effective over-the-top weed control option in grain sorghum that became available to Texas sorghum producers in late 2012. I have reviewed Huskie in three previous Sorghum Tips. Since 2012, Bayer CropScience has updated the label in both late 2013 and late 2014. As with any new herbicide our understanding of the herbicide often evolves for a few years after release—the effectiveness of its control of numerous weeds, optimizing timing and application, potential residual/rotation issues, etc.

For a recently updated summary on Huskie that includes changes in rotation restrictions (shorter for certain small grains, other crops added), review the AgriLife Extension PowerPoint at http://lubbock.tamu.edu Key points about Huskie include:

- Bayer’s label continues to recommend the inclusion of atrazine with Huskie to improve weed control (sorghum up to 12” tall), but Huskie applications are now also labeled to 30” tall (though this may not be a good idea—see below). Follow other label suggestions for suggested additives.

- Some sorghum that is drought stressed might struggle to recover from Huskie applications, but then weeds are in the same situation thus control may be reduced.

- Some leaf burn (but not crop injury) to grain sorghum is expected with Huskie on sorghum, and although the label does not state this Bayer staff in Texas recommend the inclusion of 1pint of iron (Fe) chelate (or possibly 1 lb. of iron sulfate, not tested) with Huskie to reduce injury potential, especially under stressful conditions.

- Remember that your pre-plant/pre-emerge weed control strategy for grain sorghum remains your most important weed control decision in grain sorghum. The fact you can apply Huskie later should not be seen as an excuse to delay, and Huskie applications even if by 12” tall are no substitute; use Huskie to catch the escapes. For many producers this is a combination of Dual (metolochlor) and atrazine (or possibly propazine).

Huskie and Cotton Rotation

As noted before, AgriLife weed scientists and others in the High Plains and elsewhere, especially on sandier soils, are tracking rotation questions of Huskie-treated ground back to cotton. The label says “field bioassay.” I noted a year ago that some apparent low levels of cotton injury were observed in cotton and peanut after 2012 Huskie use in grain sorghum. In 2014 we had significant injury issues in some cotton fields in the South Plains (Lubbock) region. This included fields that were treated in 2013 with Huskie alone, eliminating possible injury concerns from atrazine.

Why the cotton injury? AgriLife weed scientists (Keeling, Dotray) who follow weed and herbicide issues in the High Plains note that most fields with significant injury were as follows: sandier soils, dryland and drip-irrigated fields (which meant reduced moisture in the soil surface), and region-wide we had bone dry soils from late summer 2013 to Memorial Day weekend 2014 which led to minimal biological/chemical degradation of Huskie residual.

Bayer staff note the Huskie label will for now remain “Field Bioassay” for cotton and a few other unlabeled crops rather than offer a rotation restriction in terms of months. It is possible that rotation to crops like cotton the following year after Huskie use might eventually include provisions (as some other herbicides do, and Huskie currently notes for alfalfa) for a combination of inches of rainfall and/or irrigation in order to plant certain rotation crops.

Sugarcane Aphid “Tolerant” Grain Sorghum Hybrids: Part II – Commercial Hybrid Yields

Statewide

In the January 29 Sorghum Tip – Part I, I discussed ‘What does tolerance to the sugarcane aphid mean?’ It is important to have a correct understanding of how these tests were intended to be used, their results—and what the SCA-tolerance results do NOT say. The caution is that we would be mistaken to read too much into the results and assume that preliminary tolerance in controlled settings will indeed translate into field tolerance where environmental conditions are introduced.

I have searched the entire Texas A&M AgriLife Research Crop Testing Program database dating back to 2005 for results on the current commercial hybrids that have been designated by their company as tolerant to SCA. (Pioneer 83P56 is a new release and has not been tested by AgriLife.)

Results are reported for Central & South Texas rainfed, Central & South Texas irrigated, limited data for Northeast Texas rained, as well as Texas High Plains irrigated and dryland. A couple of hybrids have not been tested in several areas of Texas. Because all hybrids were entered by the companies in only a portion of the trials, I can’t directly report the yields. That wouldn’t provide accurate comparisons among these hybrids. Thus the reporting is as follows:

- The number of reported test locations.

- The average percent relative difference in yield vs. the trial average (only for the sites the particular hybrid was entered).

- The average ‘Percentile’ Rank, e.g., this tells how a hybrid compares to all other hybrids; the higher the number the better performing the hybrid’s yield. A hybrid that is in the 80th percentile means it is in the top 20%, or yields better than 80% of the hybrids.

- The actual yield only at the sites where the hybrid was tested. This is important in understanding the hybrids yield and how much chemical control costs for SCA (Transform, Sivanto) are relative to yield and potential revenue. Hybrids in a low-yielding environment would lose more of their revenue to insect control costs. You can’t compare the yields of these hybrid to each other using this number (they represent a different combination of test sites).

South & Central Texas

Rainfed Results^

|

Hybrid |

# of Yield Tests | Avg. % Relative Yield Difference | Avg. Percentile Rank |

Avg. Yield at Test Sites |

|

S.P. KS310 |

Hybrid not tested at any location, 2006-2014 | |||

|

S.P. NK5418 |

Insufficient data (< 3 sites) |

|||

|

S.P. K73-J6 |

3 |

-3.5 % |

35 |

4,333 |

|

S.P. SP6929 |

6 | +0.8 % | 51 |

4,867 |

| Dekalb Pulsar |

Hybrid not tested at any location, 2006-2014 |

|||

| DKS37-07 | 5 | +1.4 % | 50 | 5,561 |

Irrigated Results*

|

Hybrid |

# of Yield Tests | Avg. % Relative Yield Difference | Avg. Percentile Rank | Avg. Yield at Test Sites |

| S.P. KS310 |

Hybrid not tested at any location, 2006-2014. |

|||

|

S.P. NK5418 |

3 | -20.4 % | 13 | 5,772 |

|

S.P. K73-J6 |

6 | -6.2 % | 31 | 6,807 |

| S.P. SP6929 | 9 | -7.8 % | 26 |

6,990 |

| Dekalb Pulsar |

Hybrid not tested at any location, 2006-2014. |

|||

|

DKS37-07 |

Insufficient data (< 3 sites) |

|||

Test sites with 2 or more years:

^Gregory, Danevang, Thrall & Granger

*Weslaco/Monte Alto & Hondo

Northeast Texas

Only three trial sites contained any of these six hybrids. Data from Prosper and Farmsville finds that Sorghum Partners’ NK5418 averaged 5,491 lbs/A, or +3.7% above trial average, and a percentile of 63.

Texas High Plains – Dryland

Rainfed Results

|

Hybrid |

# of Yield

Tests |

Avg. % Relative Yield

Difference |

Avg. Percentile

Rank |

Avg. Yield at

Test Sites |

|

S.P. KS310 |

8 | -17.2 % | 23 | 2,360 |

| S.P. NK5418 | 9 | +12.9 % | 75 |

3,289 |

|

S.P. K73-J6 |

Hybrid not tested at any location, 2006-2014 |

|||

|

S.P. SP6929 |

2 | -3.9 % | 29 |

2,882 |

| Dekalb Pulsar | 8 | +3.6 % | 58 |

2,953 |

|

DKS37-07 |

9 | +6.6 % | 65 |

3,104 |

Texas High Plains – Irrigated

Limited Irrigation Results

|

Hybrid |

# of Yield

Tests |

Avg. % Relative Yield

Difference |

Avg. Percentile

Rank |

Avg. Yield at

Test Sites |

|

S.P. KS310 |

Insufficient data (1 site) | |||

|

S.P. NK5418 |

4 | +6.9 % | 74 |

5,555 |

|

S.P. K73-J6 |

Hybrid not tested at any location, 2006-2014 |

|||

| S.P. SP6929 |

Insufficient data (1 site) |

|||

| Dekalb Pulsar | 2 | -5.6 % | 30 |

4,934 |

|

Dekalb DKS37-07 |

2 | +2.7 % | 59 |

5,289 |

Full Irrigation Results

|

Hybrid |

# of Yield

Tests |

Avg. % Relative

Yield Difference |

Avg. Percentile

Rank |

Avg. Yield at

Test Sites |

|

S.P. KS310 |

No test data | |||

| S.P. NK5418 | 4 | -12.6 % | 17 | 6,595 |

| S.P. K73-J6 |

Hybrid not tested at any location, 2006-2014 |

|||

|

S.P. SP6929 |

No test data | |||

| Dekalb Pulsar |

Insufficient data (1 site) |

|||

| Dekalb DKS37-07 | 4 | -6.5 % | 39 |

6,828 |

Conclusions

Overall, the data for South and Central Texas suggest that the yield trial results of these six hybrids where tested, are average at best in rainfed conditions, and below average in irrigated production. As noted in the previous Sorghum Tip, if any SCA-tolerant hybrid has lower yield relative to trial averages or hybrids you like, you will continue to plant your preferred hybrid. Producers may conclude that {Good yield + SCA control costs – the uncertain risks of SCA} are preferable to a tolerant hybrid with low yield potential; but current hybrids that are designated at SCA-tolerant-based on preliminary greenhouse testing-may not retain field tolerance under field environmental conditions. In spite of this, some producers may elect to include some acres of these hybrids if concerned about SCA. Planting at least some acres of hybrids with early indication of tolerance on your farm—even if 20% of total grain sorghum acreage—can still contribute to your IPM approach on at least some of your acres if the tolerance translates to the field.

As we await observations of field response to these and other hybrids we probably don’t have the needed hybrids with tolerance yet in the commercial market place that will enable us to move forward without dependency on chemical spray control, which is going to curtail grain sorghum acreage.

Sugarcane Aphid “Tolerant” Grain Sorghum Hybrids: Part I – What does ‘Tolerance’ mean?

Statewide

Here I will describe what is meant by the designation of some grain sorghum hybrids as tolerant to the sugarcane aphid (SCA). Two companies (with six hybrids, see the Dec. 10, 2014 edition of Texas Sorghum Insider) have announced they have grain sorghum hybrids that tested as tolerant in independent testing conducted by USDA-ARS entomologist Dr. Scott Armstrong, Stillwater, OK. (One additional hybrid has been announced by a third company as having some level of tolerance, but it was not to our knowledge part of the USDA tests.) Test criteria include known tolerant checks including ‘Tx2783’, which is in the background of some commercial hybrids (though not necessarily the hybrids designated as tolerant). These tests were initiated by introducing a small number of SCA on 2-3 leaf seedlings and evaluating after ~15 days. In general—but not with certainty—the results of tests like these are believed to translate with some level of confidence to plant response to aphids on older plants. But keep in mind there is no substitute for evaluating sorghum hybrid response to sugarcane aphid in field conditions—other than field conditions! The field introduces factors that don’t exist in a growth chamber/greenhouse where these USDA tests were conducted. Test measurements include:

- Foliar chlorosis/plant death ratings from 1 (normal) to 9 (dead) {1-3 is resistant/tolerant; 3-6 is moderately resistant/tolerant—Dr. Armstrong notes that even hybrids of ratings of 5 to 6 may confer helpful tolerance to SCA; 6-9 is susceptible}.

- Height differential between normal plants and those infested with SCA (the greater the height difference between [normal – infested], the more susceptible).

- In some tests, aphid numbers per plant may be reported.

First, even ‘tolerance’ does not mean the plants can’t be affected by the aphid. Tolerance certainly does not mean ‘resistance.’ Field observations as well as lab studies suggest that SCA-tolerant grain sorghum hybrids may have as many aphids per leaf as susceptible hybrids, but the damage to the plant (leaf death and ultimately yield) is less than that on susceptible hybrids. Tolerant hybrids may be just as subject to honeydew and gummy harvest conditions as susceptible hybrids. Thus as the Dekalb and Sorghum Partners news releases note, tolerant grain sorghum hybrids are part of an integrated pest management (IPM) approach addressing SCA in Texas. The current list of company designated tolerant grain sorghum hybrids identified in USDA screening tests—as previously reported in Texas Sorghum Insider—is noted below.

| Hybrid | Maturity | Grain Color | Head Type | Notable Characteristics |

Sorghum Partners

| KS310 | Med-early | Bronze | Semi-open | Best suited for double crop, late |

| NK5418 | Medium | Bronze | Semi-compact | May tiller more under favorable conditions |

| K73-J6 | Med-long | Bronze | Semi-open | Staygreen |

| SP6929 | Med-long | Bronze | Semi-open | Targeted for South Texas |

Dekalb

| Pulsar† | Med-early | Bronze | Semi-open | Greenbug Biotype I resistant (main current biotype) |

| DKS 37-07 | Med-early | Bronze | Semi-open | Greenbug Biotype I intermediate resistance |

SCA Testing Results from Other Companies Apart from Reported USDA Tests?

Dr. Armstrong’s testing agreement with companies likely requires their permission to report results. He continues additional testing of more commercial hybrids. If a company you are interested in has not announced any SCA-tolerant hybrids you should not necessarily assume that they have no SCA-tolerant hybrids; they may not have arranged for or completed independent testing yet. Producers may ask their grain sorghum hybrid seed representatives if their company has tested for SCA tolerance, and if so what are the results. One additional company designated SCA-tolerant hybrid: Pioneer recently announced medium-long 83P56 has defensive traits against SCA, but the method (aphid screening, field evaluation) or source of results (internal or external) were not reported.

SCA-Tolerant Hybrids and Yields

In our next Sorghum Tip Texas A&M AgriLife will report what yield data we have on the above seven hybrids relative to other hybrids in our Crop Testing Program extending as far back as 2005. If an SCA-tolerant hybrid has lower yield relative to trial averages or hybrids you like, then you may elect to continue to plant your preferred hybrid. Remember, though, if you are concerned about SCA then planting at least some SCA-tolerant hybrids on your farm—even if 20% of total grain sorghum acreage—can still contribute to your IPM approach on at least some of your acres. If you wish to take an early look at CTP hybrid trial results for these hybrids, consult http://varietytesting.tamu.edu/grainsorghum/index.htm and also note the link to archived grain sorghum hybrid trial reports on the right (back to 2005).